This paper was originally delivered as a response to ideas around the Anthropocene, and was part of ‘Where are we Going, Walt Whitman’, the Gerrit Rietveld Academy Studium Generale, Amsterdam (2013).

One of the things we think about in art school is how our experiences of the world can be shared through their re-presentation as images and forms. Understanding something of the structure of these representations is clearly crucial to the work we do. This paper will look briefly at the Anthropocene, at the images that help define this idea, and at how the aesthetics of these images may in fact be undermining, rather than supporting, the importance of the ideas held within the concept of the Anthropocene.

In this Studium Generale we have been looking at two recent natural disasters and their impact on the communities they hit. One was Hurricane Sandy, an incredibly violent storm that ripped up the east coast of the USA in October 2012, and was widely reported in news broadcasts all over the world. Meteorologists think this storm was so much more violent than those in the past because of the effects of global warming on sea levels and hot and cold water flows in the north Atlantic.

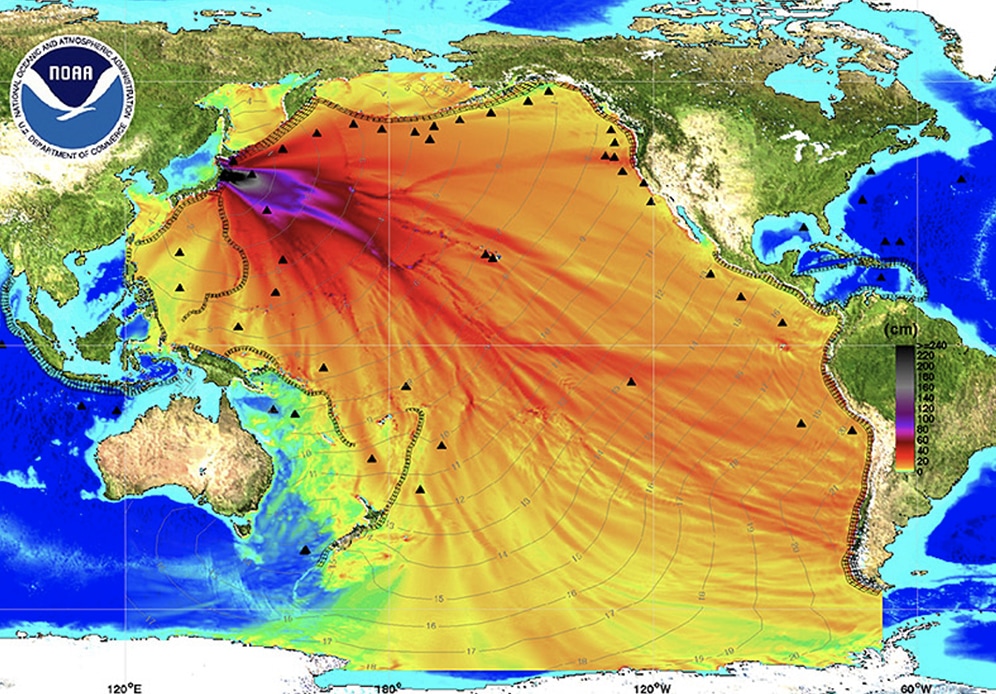

In relation to this, we also considered the earthquake and resultant tsunami that hit the east coast of Japan in March 2011, and specifically, the damage done to the Daiichi nuclear installation near Fukushima.

These events have been described in terms of The Anthropocene. This term was initially coined to mark the evidence and extent of human activities on the earth’s ecosystems at a global level, and to mark the significance of man-made changes to the earth’s atmosphere during the last century. It is officially defined as: “denoting the current geological age, viewed as the period during which human relating to or activity has been the dominant influence on climate and the environment.”

Although it seems beyond dispute that man is changing the environment of the earth, whether or not we can yet mark this as a readable geological change is still hotly disputed, and the term Anthropocene is not yet generally accepted as a new geological age, separate from the Holocene, the current term which defines the earth’s very recent past. However, popping this word into a search engine quickly reveals that the term, first in print in 2000, is already in use by many different cultural and political groups, for many different reasons. So why has it caught on so widely and so fast?

I would like to propose that the S-word is in play here, but first let’s return to Hurricane Sandy.

Looking for words to describe the level of damage inflicted by the hurricane, newspapers and websites around the world described the flooding as ‘biblical.’ In a part of the world not generally associated with such disasters, it didn’t make sense to try to locate this in relation to other events, and the press went to the narratives that make up their cultural image bank, and that therefore also make up the inner image world of the people in that culture.

The Gates of Hell. I know that the photo relates to a real life event—Hurricane Sandy—on the news—in the city my friend lives in—but it also brought up a host of other images I have in my head that look a bit like this. And the reason newsrooms around the world selected this image over another is because of exactly that—these images belong to a shared, cultural, image vocabulary.

This photograph was widely distributed in the days after the 2011 tsunami and the word that comes to mind for me is apocalypse.

This image received 41 thousand likes on Facebook. It is the world turned upside down.

The earthquake off the coast of Japan in 2011, and the terrible tsunami it generated, were not the result of global warming, but the event became part of the Anthropocene when it interacted disastrously with human technology.

The wave burst over the sea wall protecting the nuclear plant, water surged through the walls and structures of the plant itself, power generators became flooded and broke down, and the absolutely crucial cooling systems were made inoperative. Nuclear fission however of course continued to occur, and the energy created began to melt the containers that protected the immediate environment of the plant from this deadly technology.

All of this was followed in homes and offices around the world, on televisions and laptops. Images of terrible frightening events. But for most of these world citizens, both the tsunami and the hurricane unfolded as image events, stories that, however disturbing, would not impact directly on their own lives. For those directly involved in the disasters this was horror, life threatening and world changing. But for most people engaged by this ‘story’ that was not the case, they were following a narrative and looking at images that would not directly impact on them. It is on this more distanced interaction with an event that I want to focus.

We have already seen in this Studium Generale how man’s efforts to distance himself from the most extreme aspects of nature—to create a divide from nature—lay at the heart of the Enlightenment, and then the Modernism projects. We have seen that technology has distanced us from the hardships of the weather, from extremes of cold, heat, wet, from the daily necessity to hunt for or grow our own food. We can now look at nature rather than having to exist fully within it. We have managed to step back somewhat from the hardships of direct co-existence with our little bit of the planet, and it has become an object, an object of contemplation.

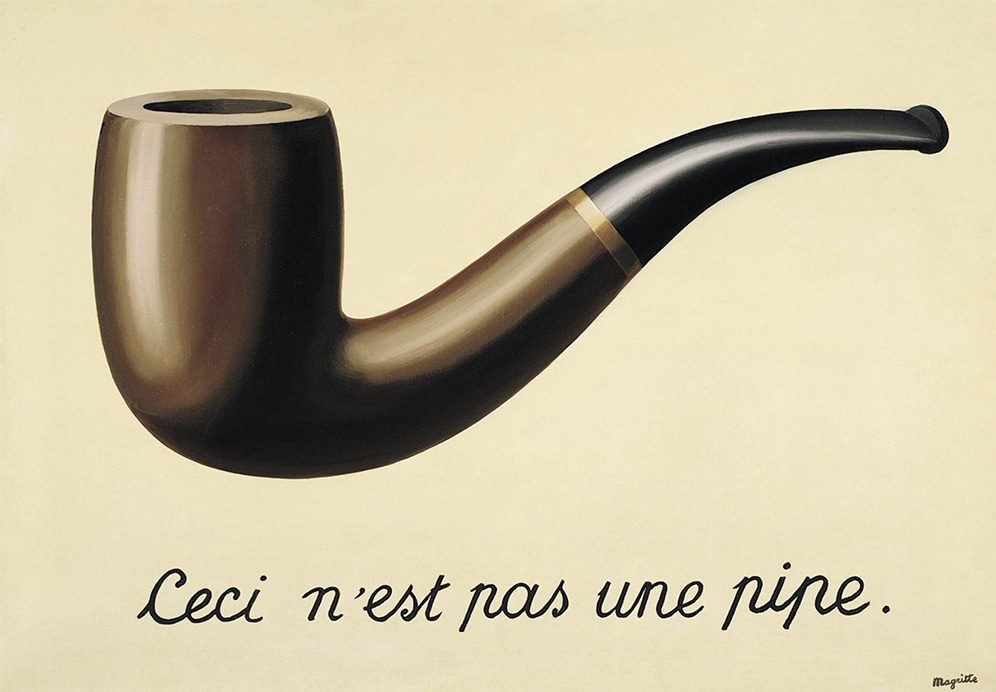

This process of distancing ourselves from the elements of our world is the history of civilization. The idea that later today there may be ‘no more coats and no more home’ can seem irritating to even consider. But in the superhybrid Googleworld that we now occupy, where so much of our information comes to us virtually, via the screen, it is useful to stop for a moment and re-iterate the fundamental notion that a thing and its representation are not the same.

To do this, I would like to bring in an idea that never seems to get much air time when considering our responses to difficult contemporary events, and this is the Sublime. If we go right back to Emmanuel Kant’s ‘Pictorial Sublime,’ in The Critique of Judgment of 1790, we read that Kant considered the ‘sublime’ to be an experience that consists in a feeling of the superiority of our own power of reason, as a supersensible faculty, over nature.

Kant stated that we can consider nature as sublime when we consider it as “a power that has no dominion over us.” We have this feeling when we experience nature as fearful, while knowing ourselves to be actually in a position of safety, and so without having to be afraid. In this situation “the irresistibility of [nature’s] power certainly makes us… recognize our physical powerlessness, but at the same time it reveals a capacity for judging ourselves as independent of nature and having a superiority over nature… whereby the humanity in our person remains un-demeaned.” Kant’s examples of this experience include looking at images of hurricanes, thunderclouds, volcanoes, and earthquakes (not experiencing these actual events).

The feeling associated with the sublime is a feeling of pleasure in the superiority of our reason over nature, that is, our technological ability to distance ourselves from the risk of death or extreme physical discomfort (it’s hard to remain ‘un-demeaned’ while scrabbling to save your life). The sublime also necessarily involves displeasure however. This is the other side of ‘distanced’ awareness of our actual physical powerlessness in the face of nature’s might. Kant describes this double-sidedness as a “movement of the mind” which “may be compared to a vibration, to a rapidly alternating repulsion from and attraction to one and the same object.” Kant also describes the feeling of the sublime as a “pleasure which is possible only by means of a displeasure” and as a “negative liking.”

These polar bears are stuck; we know that without ice they will eventually die of starvation. This is a horrible image. And yet, whenever global warming is mentioned in the press, it is images like these that we see. I would like to suggest that these images do not engage us in the imminent disaster that is global warming, but in fact do the opposite. They allow us to experience the sublime, this pleasurable vibration between repulsion and attraction, while sitting in the comfort of our homes, happily distanced from the frightening reality that these images may represent.

The reason the Anthropocene is a subject for us today is that one of its results is global warming. It may be measurable from the residues of the first nuclear explosion, but it is a subject of interest to a broad swath of people because human development of technology is having a massively negative impact on the planet as an environment suitable for human life. So do the images we are shown in order to help us understand global warming end up making us feel safe? This is an uncomfortable idea but clearly there is some sort of a problem with message delivery. Otherwise, surely, we would all agree to do something about this? Why do we not vote out our neo-liberal governments and vote in some people who might actually do something? Somehow, we continue to believe that the problem is not here, it is not now, and it is not us.

We don’t quite believe that the problems of the polar bear are about to be our problems, we still feel safe. The message is not getting through.

Let’s think about the coverage of the Fukushima nuclear disaster again.

A more contemporary reading of the sublime is that it comes into effect today when we think about technologies that threaten to overwhelm us—contemporary weapons of war, cloning research, nuclear power… It was shocking when we realized that the Daiichi nuclear plant had become inundated with water, and that its functioning may be impaired, but it was a nuclear plant built on the edge of an earthquake and tsunami zone, so they must have worked out how to deal with this, right? At this point, in the news timeline of the event, the tsunami was, for most of us not directly in its path, still a story, somewhat scary, thrilling.

The story moved out of the sublime and into our faces at this point.

Close up image of a melting nuclear core at the Daiichi plant,

Japan (2011).

Up until this moment, although there was massive empathy for the people of Japan, this was still, for most of the people here at this Studium Generale, a story we were following. Try to remember the experience as you followed it on your laptops and TV’s. There was a certain moment when the feeling around the story changed, and it was when the melt down of one or more of the cores seemed to be actually about to happen.

This was suddenly no longer a Japanese problem; it was a world problem. There was a change. Our bodies were activated in a completely different way.

By way of comparison with this way of thinking about the sublime, please consider the following image.

For anyone who has had a cigarette recently, this image will remind them of it, of the smell and feel of the cigarette on their finger-tips, of the taste of the smoke in their mouths, and the slight burn on the back of their throats as they inhaled.

This is not an image in the register of the sublime.

We cannot distance ourselves easily from nature here. Nature, we are reminded, is in our face, literally, it is us, it is our insides, our being. This image brings us back into a relationship of imminence with our bodies, our selves. The repulsive threat of death does not remain safely within the photo. Your body memory responds to what you see here and connects it directly to you. You may already be starting to gag as your body tries to eject the cancerous cells from your throat…

Distance can be calming.

The Anthropocene has been named in order to declare the magnitude of global warming, to try to wake people up to an engagement with our planet that previous generations could not have imagined. It is an enormous idea. Can man really now harness enough power to affect the earth on a planetary level? Have we really become Gods on earth? Has man become superman?

MAN never seems to mean you and me but really, it does. We are in this too; we have superhuman powers to change the flow of the oceans, the melting of the polar ice, the movements of wind and rain. This idea is empowering. It is frightening to have this power, but there is also something rather fabulous and attractive about the idea. This is the vibration of the sublime. By just sitting at home, protected, quietly using up energy and resources, we are acting like the gods of Olympus, changing the world. We are superman.

I would like to suggest that this aspect of the Anthropocene is much of the reason the term has caught on so widely. Not because it moves people to the actions we all so desperately need to take, but quite the opposite, that, like a good thriller, it is both exciting and pacifying. We can be part of something huge without getting our asses out of bed.

The history of man imagining himself as superman, of course, has not been good.

One of the fundamental problems in engaging with the idea of global warming is that it is simply too big for us to see, and this takes us back again to Kant, this time to his idea of the Mathematical Sublime, in which the frisson of trying to imagine a term like infinity, is, because of our temporal bodily existence, just impossibly hard to come to terms with.

Climate change is also a mathematically sublime idea or object. As bodies we cannot see it in its wholeness. Our knowledge of it is based on modeling by super-computers, and it can only be ‘seen’ by the non-human eye. As we watch the world through our laptops, and with Google specs, we need to think hard about what it will mean to see with non-human eyes. We may soon all be wearing the Palo Alto specs but in geological or evolutionary terms our bodies are not long out of the cave. The anti-smoking image showed us that we see with those bodies just as much as with our intellects, and that our bodily responses are fundamental to the reception of an image or idea. Is it life or death? Do we fight or flee? Are we attracted or repulsed? Images generate affects, and primal responses still matter.

Aesthetics matter. The right aesthetic can completely nullify the supposed content message of a news item. Advanced capitalism knows this; we live in an affect economy. We no longer buy things because we need them (the economy would crash tomorrow) we buy things because of how they make us feel. The market ruthlessly employs aesthetic techniques to massage our emotional triggers, to target our desire and therefore consumption at an unconscious level.

In his thinking on the Simulacrum, Baudrillard suggested that by the 1980’s already, art had become an aesthetic front that covers up this trans-aestheticised economy, that the whole world had become a work of art; that Disneyland is the cover that saves us from having to face that the whole world is Disneyland. News coverage is edited to produce exciting images to maintain ratings, and our engagement with the larger world is mostly through the newsfeeds of our computers and phones. Whatever feed we use, Google image search shows us the images are all very similar. So what chance has the professional image-maker, the artist, in making a work of art that does anything more than act as Baudrillard’s aestheticised front? That is more than a quote from the subject of the day, and is actually a politically ‘affective’ action?

If a ‘politicized’ art practice ends up offering the viewer yet another sublimely distanced engagement with a subject, that viewer may consider him or herself to have acted politically by interacting with the work, and the artist may consider him or herself politically active by making such a work, when all that actually happened was that both parties were pacified by a vicarious engagement with a marketed entertainment that in no way interrupted their passive flow of consumption.

Should we give it up? Can art ever pierce our aestheticised and distanced existence? I still believe it can, but these are questions that each of us here in art school needs to answer for ourselves, one work at a time.