The Isolation Paintings Ghost and Silence, The Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, 1999.

The Isolation Paintings Ghost and Silence, The Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, 1999

Sarah Tripp · Collective Gallery, Edinburgh. Catalogue essay (1999)

Bringing Bad News

from Nowhere

In 1890 William Morris responded to industrial squalor in Britain with his own earnest crusade, a heady mix of a retreat into romantic poetry and a leap into utopian socialism. Morris tried to give form to his infant utopia in writing, oratory and the elevation of the decorative arts. In his publication News from Nowhere Morris describes a dream of sunny meadows, timber dwellings, meaningful labour and happy, healthy social interaction—an anti-industrial society. While utopians like Morris share their dreams, so the disenfranchised can share their optimism: someone has to describe our nightmares.

More than just the spectre of industrialisation now haunts our lives, and as the problems of the west multiply we compensate with boundless visions of electronic unification. Our Armageddon is coming in the form of the Deep Impact of a comet or an alien invasion on Independence Day, but we save ourselves with technology. There are however a number of people who are forging uncompromising images of our anti-utopias. These people present the worst possible outcome. Their visionary power reclaims our black fear of an immanent and cruel retribution… not all visions have to do with the future or the hereafter.1

Some of the men and women who have contributed to a vision of a western anti-utopia are more reluctant than others; E. M. Cioran proclaims Everything I have been able to feel and to think coincides with an exercise in anti-utopia2, others like sufferers of Multiple Chemical Sensitivity (M.C.S.) are unwilling participants. These people are living the western consumers nightmare. Janice McNab recently visited New Mexico where she talked with a number of people with M.C.S., took some photographs of where they live and has been researching the condition. McNab is depicting anti-utopia as it creeps into our everyday life, not as post-apocalyptic doom but as the waking nightmare of people disabled by chemical products.

M.C.S. can be caused by exposure to a variety of chemicals that are commonly encountered, like pesticides, perfume, building materials and vehicle exhausts. Research into the effects of chemicals on humans is far from complete, and the public are regularly exposed to supposedly safe levels. Particularly at risk are workers in heavy industry, war veterans and communities exposed to toxic waste dumps, pesticide spraying, ground water contamination and industrial pollution. Chemical injury is not fully understood and many doctors are unwilling to accept M.C.S. as legitimate, often accusing sufferers of being techno phobic and chemo phobic. There is some research however on the symptoms which M.C. S. people experience and it is very real pain and suffering. The symptoms include headache, fatigue, respiratory difficulties, gastrointestinal problems, altered brain chemistry, chemically induced cancers, cardiovascular disease, neurological injury and birth defects. Never unreal, pain is a challenge to the universal fiction. What luck to be the only sensation granted content, if not a meaning?3

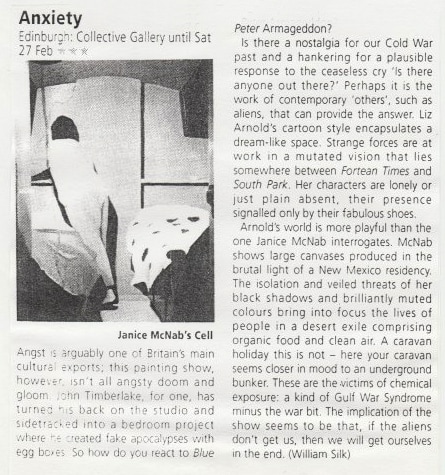

It is hard for people with M.C.S. to form communities or a collective identity because their symptoms vary hugely. They are often also allergic to other people and most environments so they usually migrate in search of a toxin free space. Geographical distance and personal suffering test friendships, relationships and alliances. Recovery can only be made in open clean air and in ceramic or metal accommodation. Anxiety, painted by McNab on return from New Mexico, depicts the minimal accessories to this kind of painful life: oxygen tank, telephone and portable cooking rings. In Cell, the home of the hermit and the prisoner, a sufferer of MCS is inside a ‘safe’ shelter at night. Something has been emptied out of or removed from this room. Despite the human presence there is a conspicuous absence here.

The paintings, their titles and texts about MCS presented in the Collective Gallery cause me anxiety—very few of us like to see suffering. So might I be responsible for these people? It is hard for us to believe in random disaster; in fact it is almost impossible not to give an ethical dimension to the evils that befall us. From the primitive pagans onwards, ritual and belief have helped explain the world. Our knowledge of environmental illness presents us with an ethical as well as a medical dilemma—consumerism, capitalism, and our political and moral consciousness are involved.

From the reforming Puritans on, western society has considered its being to be an enterprise to make profit for the glory of God. To choose the self over God is the sin of pride, and the piety endorsed through Luther and Calvin not only enslaved man to God but also bound him to hard and obedient work during the birth of industrial capitalism. Man existed as depraved and corrupt; pleasure became synonymous with sin and work with salvation—societal harmony and capitalist productivity is thus assured through Puritan ethics. These links still function in secular consumer society but have been paradoxically adapted to accommodate the pleasures of consuming. One might feel guilty about consuming so much, but it is undeniable that it is a pleasure that feels like a necessity.

Our markets, our shopping avenues and malls mimic a new-found nature of prodigious fecundity. These are our valleys of Canaan where flows instead of milk and honey, streams of neon on ketchup and plastic—but no matter!4

Is our consumer pleasure inadequate? What are we purchasing and possessing? As consumers, satisfaction of our needs means adherence to the values of capitalism, but the chemically injured are unwitting rebels in this system, they are forced to reject these values.

There are still the remnants of guilt associated with pleasure and consequently our relentless desire for products is justified by the need for capitalist productivity. By attaching guilt to pleasure we can begin to unmask our participation in a system, which relies on us to be complicit with, amongst other things, a chemical industry which is harmful. The painting Van works as a harbinger of bad news for all of us. Janice’s paintings refer not to dark, subconscious fears but to quiet frustration and reluctant life choices. Our empathy is the megaphone of our conscience; it is hard not to listen.

It is unlikely that there will be a fundamental change in our approach to the use of chemicals until the problem of MCS reaches critical mass. The people McNab met hoped that she would take information about their plight into a normal environment. If you can get across to people that there’s a plausible case that environmental problems will increase the incidence of violence, then that makes environmental issues more than just lifestyle, or quality of life, or aesthetic issues.5

There is a quiet and more logical fear that I encounter through these paintings however. The paintings are reserved and this slowness in conjunction with the facts about MCS makes morally difficult work for the viewer. The work is believable because it is cradled by our knowledge of capitalism’s ruthlessness. Rebellious art also ends by revealing the ‘We are’ and with it the way to a burning humility.6 This work mediates between what we know and what we fear for ourselves—a retribution for the sins that have been hidden from us by the calculus of objects7 that we do daily. Art is a man’s embodied expression of interest in the life of man,…8 Through this work I have registered the lives of people restricted, transformed and politicized by the negative effects of consumerism. Bad news for our consumer paradise.

NOTES

- 1. Umberto Eco, Apocalypse Postponed, Indiana University Press, 1994 (referring to George Orwell, 1984)

- 2. E.M.Cioran, The Trouble with being Born, Quartet Books Ltd, 1993.

- 3. Ibid.

- 4. Jean Baudrillard, Selected Writings, Stanford University Press, 1988.

- 5. Homer-Dixon quoted by Mark Kingwell in Dreams of Millennium, Faber, 1997.

- 6. Albert Camus, The Rebel, Penguin Books, 1951.

- 7. Jean Baudrillard, Selected Writings.

- 8. William Morris, Selected Writings and Designs, Penguin Books, 1962.