The Isolation Paintings, Installation, Stroom, The Hague (2020)

The Isolation Paintings, Installation, Stroom, The Hague (2020)

In 2020, I re-exhibited a group of Isolation Paintings that I had created twenty years before. Europe was in the first phase of pandemic lockdown and I thought there might be value in looking back to this record of the hidden lives of women who were getting sick from the conditions of contemporary life.

Bettina, Fabienne, Jacqueline, and many others had found themselves caught in the vanguard of a destabilised relationship to our environment that we were all suddenly facing. These women did not have contact with a new virus however. Their bodies had maxxed out on the invisible chemical load of daily life, been made sick by the everyday toxic load given off by cleaning fluids, cosmetics, carpets, pesticides, paint, and fuel. Survival meant not going to the office, or living in the city, it meant eating expensive biologically produced food, keeping off busy streets, and away from loved ones.

These paintings are documents from a time when such self-isolation was commonly interpreted as crazy and self-indulgent. The way these women had to live is, however, the way we all began living during lockdown. As we struggle to process the reality of a pandemic that spreads through air, I hope these ghosts of the past somehow press on the idea that our social lens can re-focus, and that wanting things to go back to ‘normal,’ might not be the most life-saving thing to want in this, our new world.

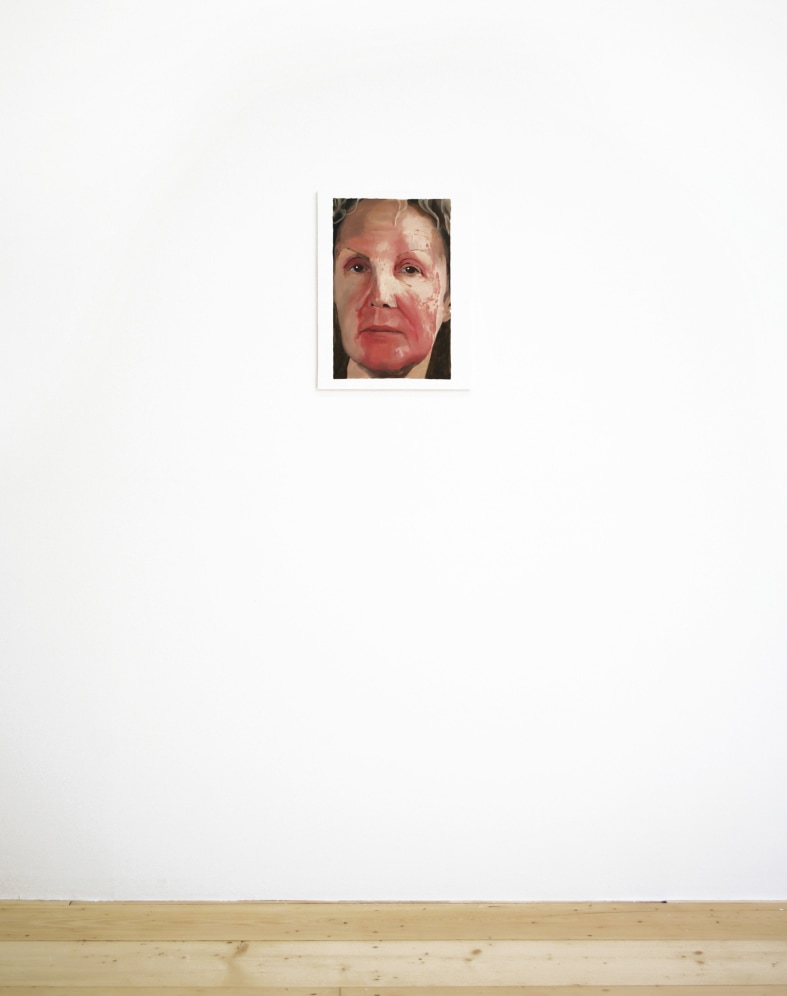

Fabienne has not been outdoors since 1981, Installation, Stroom, The Hague (2020).

Bettina, Installation, Stroom, The Hague (2020).

ARTS JOURNALIST MOIRA JEFFREY REVISITS THE ISOLATION PAINTINGS · PART OF “THE NEW WORLD,” STROOM, THE HAGUE (2020)

The New World

A yellow table sits in front of a radiator covered in cloth. On the table top there are piles of protective gloves and a portable hotplate. A black electrical cable snakes its way across a bare plaster wall. This bleak domestic interior is titled Anne’s Kitchen, yet it seems impossibly distant from the familiar comforts of food and domestic warmth.

In 1998, Scottish painter Janice McNab travelled to the United States to research a new series of paintings, and began a political journey that she later described as a “slow-dawning shock.” In New Mexico she had arranged to meet members of a community of outliers. These were people suffering from Multiple Chemical Sensitivity, with ravaged immune systems and chemical poisoning. Once they had lived ordinary urban lives as office workers, spouses or parents, now they eked out solitary, improvised existences in the desert. They were living in caravans and home-built shacks to escape triggering symptoms such as respiratory distress and extreme fatigue brought on by exposure to the chemicals released by contemporary furniture, electrical goods and cleaning agents. On her return to the UK McNab sought out other sufferers. There was the elderly Fabienne, wrapped in a faded dressing gown, who had not ventured beyond her closed front door for two decades. And Anne, who protected her skin with gloves and had stripped the wallpaper and paint from her walls to avoid immune reactions. These were people forced to live under principles of severe restriction, in isolation and often in enforced poverty, but they were communicating with each other to share specialist knowledge, trying to support others in the same circumstances.

In 2001, when I first wrote about these paintings, I wrote with a sense of anger and helplessness. These were not individual portraits so much as the flesh and blood landscape of neo-liberalism: where suffering was minimised, privatised and domesticated. In them the conditions of capital seemed inescapable. These women had been injured in their workplaces, by domestic pesticide treatments, by exposure to agrochemicals or by mysterious and unknown exposures in everyday life. Often they had been told that their symptoms were psychological, but McNab’s paintings told me that capitalism was making them sick.

McNab’s working practice was alert to the complex politics of rendering her subjects visible, the careful consent that was needed to tell their stories. She has described the rituals that were necessary to meet them: the use of scent-free soap and shampoo, washing her clothes in bicarbonate of soda before meetings, refraining from the painting studio in case the lingering fumes of turpentine on her breath might cause an allergic reaction. This seems familiar to all of us now. The efforts we must go to, to make sure that we don’t accidentally kill our elderly relatives, the distanced visit to the immune-suppressed friend which is a shadow dance of affection and evasion. Fierce public debates about mask-wearing, social distancing and the politics of freedom are shadowed by the everyday rituals of repeated hand-washing, public spaces are filled with the astringent smell of sanitising gel and bleach, our public discourse with the language of anxiety and conspiracy, or the rhetoric of self-care and self-healing.

In March 2020, in the early weeks of the coronavirus shock, the American poet Anne Boyer, whose most recent book had been a raging lament about her experience of cancer care in the US medical system, published This Virus, an essay that reminded us that the encroaching fear of the pandemic was a necessary one. “Fear educates our care for each other,” she wrote. “We fear a sick person might be made sicker, or that a poor person’s life might be made even more miserable, and we do whatever we can to protect them because we fear a version of human life in which everyone lives only for themselves. I am not the least bit afraid of this kind of fear, for fear is a vital and necessary part of love.”

On this side of the first wave of the pandemic, can we even think back to February, March and April? Can we remember how the imperceptible transmission of the virus came to be visible, perceivable, have terrible consequences? In Spain, army units entering care homes in Madrid found that elderly people had been left, unwitnessed and unattended, to die alone. Satellite imagery revealed that mass graves had been dug outside the city of Qom in Iran. Shaky night-time camerawork revealed the presence of military convoys moving coffins from Bergamo in Northern Italy, where the mortuaries and cemeteries were overflowing.

In the UK, outsourced cleaners for the Ministry of Justice were deemed essential workers and travelled long distances on public transport. Some of them became ill. They were migrant workers, cleaning empty offices that had been abandoned by white-collar staff who had been sent home to work on laptops and make Zoom calls from their spare bedrooms. The lesson of the pandemic across the world has been its accelerant force. The virus is fast fuel for the decimating slow burn of poverty, racism, poor housing and precarious working conditions. The activist movements that resurged in the US and Europe during lockdown, such as mutual aid groups, reflected not only the politics of rage and despair, but the urgent necessity of fear re-shaping itself as love.

Rendering something visible is not always about seeing something new. Sometimes it is about transforming the refusal to see what is already there. A true field of research, or a field of vision, is not defined by its outward scope but by its ability to detect patterns and reap knowledge wherever it encounters them. Revisiting McNab’s anxious archive of shadows and ghosts helps us to see that the consequences of the pandemic have been long implicit in our culture. Can we make things different this time? Can we learn how to live from the isolated? And can we re-cast isolation itself as an act of empathy and necessity?

These paintings do their work by investment in their subjects. In time, consent, research. In the push and pull of oil paint on board. In the tension between the chilly fact of documentation, and the rich ambiguity of expressive mark-making. Two decades ago when the painter first encountered these stories, her subjects were marginal figures fighting to have their voices heard. Now most of us have an experience of lockdown and live with the threat of enforced isolation. Now it is the sick who might lead by example for the benefit of the well.

“We must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive,” Anne Boyer wrote back in March, “to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love. We face such a strange task, here, to come together in spirit and keep a distance in body at the same time. We can do it. I am writing this because I want the good in us to break through the layers of hateful nonsense we’ve been drowning in. I think we can be good, but we also must prepare for an amplification of evil’s evil. The time when the invisible becomes visible is at hand.”